…” this aesthetic masterpiece will add interest to a room and compliment your carefully curated contemporary modern style. We understand how important your home is and how decorating your kitchen, dining room or bedroom with classy contemporary art can help make it a place that reflects who you are. We believe in the power modern art has in creating not just a home but your home. We believe in feeling good about our home’s environment and we think you do too”.

Product literature of store-bought artwork from Home Depot.

Identifying with a consumer brand implies individuality and defines who we are in a market driven world. Veiling the interchangeable nature of consumer behavior within the workplace, the marketplace and our private domestic interiors, personal identification with a brand offers the feeling of uniqueness within a flood of sameness. Describing the collector as “the true resident of the interior”, Walter Benjamin refers to the private individual as reliant upon the domestic realm to sustain one in his or her illusions, a refuge from the workplace and outside world- a “phantasmagorias of the interior”.

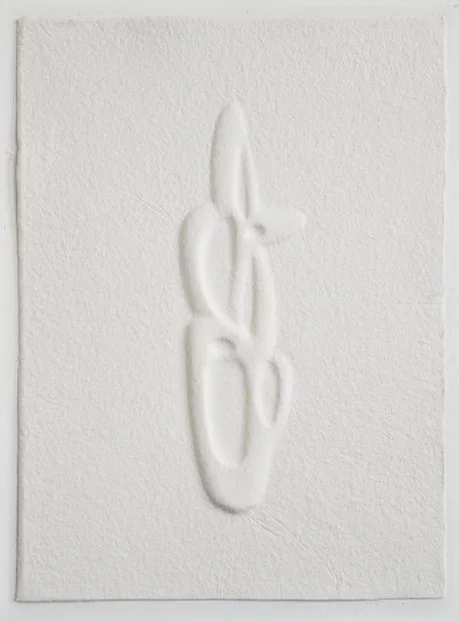

Focusing on the little-known production and distribution of corporate artwork available online through Home Depot, West Elm or Ikea and marketed to the middle-class consumer, David Baskin’s recent sculptures engage the roles of consumer, collector, and interpreter.

Acquiring these store-bought works of art which offer a consumerist spin on the utopian Modernist ideal of an “art for the masses”, Baskin made molds and casts to re-present these corporate-authored, generic artworks within their cultural origins (the studio, the art gallery, the home) revealing a kind of gleeful consumerist celebration via limitless fetish objects which collectively release us from the disappointment of failed utopias.

Cheaply produced through a globalized economic system, these corporate objets d’arts available at big box stores conflate the implied uniqueness of consumer choice with the rarified status of a work of art. Devoid of identifiable authorship and brandishing price tags and product guarantees, they extend Duchamp’s readymade gesture into the realm of mass consumption while reversing his deadpan intent; the “readymade” is now the consumer object that began as art.

In extracting these symbols of high art meant to appeal to aspirational desires of the consumer and “putting them on a pedestal”, David Baskin’s orphaned Modernist objects present the unfulfilled utopian goals of the modernist project as a kind of fodder for the fraught world of middle-class taste, engaging humor and satire as they reveal the many contradictions evident in repackaging high art to appeal to mass cultural taste.